Immunization coverage and access vary among countries of different development levels, which are often expressed using the following World Bank income group classifications: low (those with a gross national income [GNI] per capita of US$1,145 or below in 2023), lower-middle (with a GNI per capita between US$1,146–4,515), upper-middle (with a GNI per capita between US$4,516–14,005), and high (with a GNI per capita above US$14,005), displayed on the map below.

The global health community has increasingly begun to recognize the unique challenges experienced by middle-income countries (MICs), which includes both lower- and upper-middle income countries, the latter of which are typically not eligible for Gavi support. These non-Gavi-eligible MICs are home to more than half of all children born each year (66 million) and more than one-third of zero-dose children (nearly 5 million), or those who have not yet received a single dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine. Due to their struggle to introduce critical new vaccines, such as those targeting human papillomavirus (HPV), rotavirus, and pneumococcal disease, millions of children remain vulnerable to these diseases. Even in MICs that have introduced these vaccines, coverage often remains low and inequities persist, reflecting a need to improve program performance. Furthermore, some MICs also struggle to maintain coverage with existing vaccines, leaving them susceptible to deadly outbreaks of highly contagious diseases such as measles.

The potential impact of expanding immunization access and coverage in MICs is significant, especially due to the large populations in many of these countries, such as India, Nigeria, and Indonesia. One analysis estimates that the introduction and scaling up of HPV, rotavirus, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) in MICs that are either not Gavi-eligible or that have transitioned from Gavi support could have saved 70,000 lives in 2020, illustrating the importance of addressing these immunization gaps.

Steps have already been taken to mitigate the barriers faced by MICs. For example, Gavi’s MICs Approach aims to prevent backsliding in vaccine coverage and facilitate sustainable vaccine introduction in MICs, including both MICs that have transitioned out of Gavi support as well as those that have never been eligible, providing an important pathway for MICs to ramp up life-saving vaccination efforts. Still, additional strategies and multi-partner commitments are needed to ensure that the millions of children who live in these countries are protected from a wide range of preventable diseases.

Exploring MIC Data on VIEW-hub

VIEW-hub, a free platform that allows users to visualize data on vaccine introduction and use, includes the option to filter by World Bank income group, including both lower-middle and upper-middle-income groups. The following analysis, which features data that are accessible and downloadable on VIEW-hub, combines these two groups to illustrate vaccine introduction delays and immunization coverage gaps in MICs.

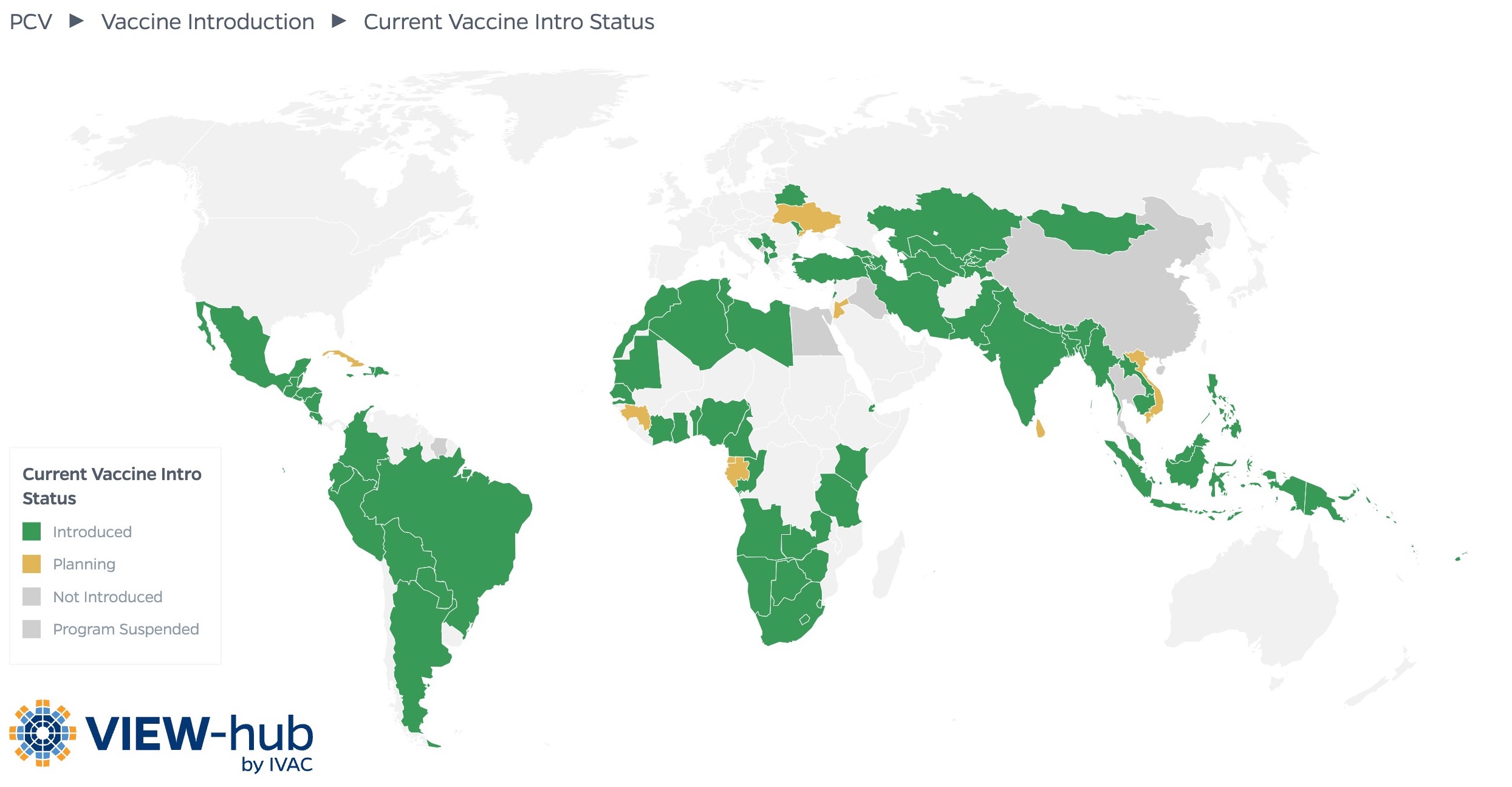

The VIEW-hub map below has been filtered to display the status of PCV introduction among MICs.

Between 2000–2024, 81% of MICs introduced PCVs into their national immunization programs, compared to 97% of high-income countries (HICs) and 85% of low-income countries (LICs). Similar trends exist for vaccines targeting rotavirus and HPV, both of which were first introduced in 2006. Just 65% of MICs have introduced rotavirus vaccines, compared to 81% of LICs and 65% of HICs. While nearly all (98%) of HICs have introduced HPV vaccines, just 73% of MICs and 46% of LICs have introduced these vaccines.

Even though non-Gavi-eligible MICs generally have higher incomes and greater DTP3 coverage than Gavi-eligible MICs, these countries are less likely to have introduced PCVs; just 78% of non-Gavi-eligible MICs have introduced PCVs, compared to 93% of those MICs that are eligible for Gavi support. Similar trends are present for rotavirus vaccines, with 62% of non-Gavi-eligible MICs having introduced compared to 79% of Gavi-eligible MICs. Interestingly, this trend does not appear for HPV vaccine introduction, with a higher percentage of non-Gavi-eligible MICs having introduced these vaccines. However, irrespective of Gavi eligibility, HPV vaccine coverage in MICs remains far below IA2030 targets.

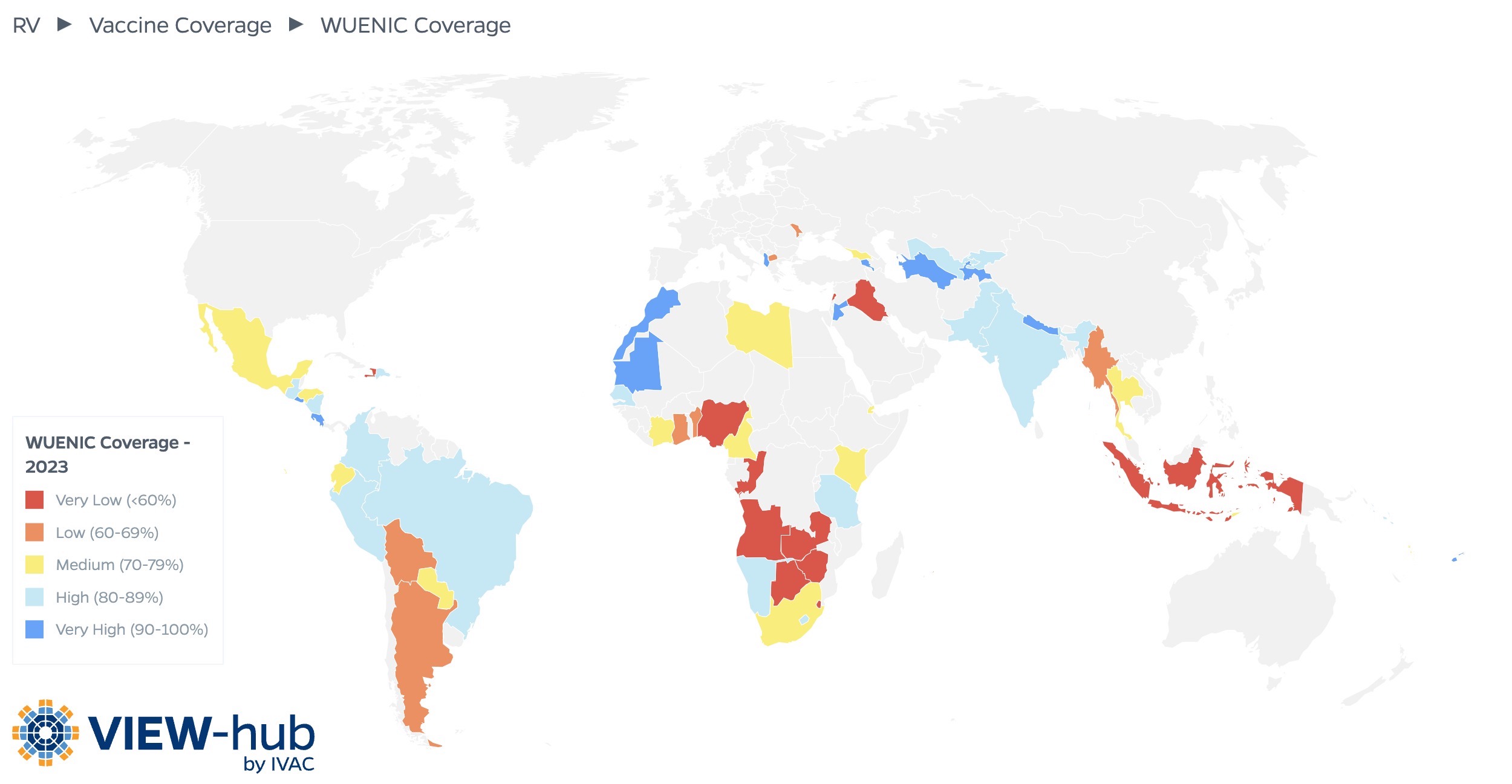

In addition to lagging behind in new vaccine introduction, many MICs also struggle to maintain high coverage with these vaccines. For example, coverage for the third dose of PCV is just 40% and 75% in upper-middle-income and lower-middle-income countries, respectively, compared to coverage of 88% in HICs. The VIEW-hub map below shows the WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage (WUENIC) data for rotavirus vaccine in MICs.

In 2023, among the 68 MICs that reported WUENIC coverage for rotavirus vaccine, fewer than half (32 countries, or 47%) reported high or very high coverage (i.e., 80% or greater) for rotavirus vaccination series completion among the target population; 14 countries (21%) reported medium coverage (i.e., 70–79% coverage) and 22 countries (32%) reported low or very low coverage (i.e., less than 70% coverage).

MIC-Specific Challenges to Immunization

MICs face unique challenges in introducing new vaccines and achieving high coverage of and equitable access to existing vaccines.

MICs may have less robust processes in place for making immunization program decisions.

Country-level decision-making processes are a key factor in a country’s ability to introduce a new vaccine or increase coverage of existing ones. MICs, specifically those that are not eligible for Gavi support, are less likely to have an established or functional National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) compared to other country groups. As these groups often provide important input into the decision-making process, MICs have more difficulty accessing, synthesizing, and contextualizing the evidence needed to make decisions about key policies, like new vaccine introductions or vaccine schedule changes. MICs may also have weak disease surveillance systems, resulting in a lack of data needed to inform vaccine-related decisions.

MICs may struggle to introduce new vaccines due to limited program capacity.

MICs have been found to experience shortages in financial, human, technical, and procurement resources, including inadequate knowledge and training about logistics, basic immunization practices, and vaccine management, which can create challenges in introducing and implementing new vaccine programs. Some MICs do not have established procurement teams or have weak procurement processes, limited experience with procurement, or weak market knowledge, which can impede decision-making around new vaccine introductions or interventions to increase coverage. Often, GNI-based eligibility for donor support does not reflect a country’s broader health system capacity, which can result in MICs struggling to effectively implement immunization programs.

MICs may have suboptimal vaccine uptake due to hesitancy and other factors impacting demand.

MICs have been found to have inadequate social mobilization, a lack of strategies related to national-level immunization communication, and weak use of mass media to disseminate information and promote vaccine uptake, all of which can impact demand for vaccines. For example, just 38% of MICs reviewed have a strategy in place to communicate about immunization activities, leading to ineffective vaccine communication. As in countries of all income levels, MICs have faced COVID-19-related changes in vaccine acceptance, with vaccine misinformation and distrust along with immunization complacency and fatigue significantly impacting vaccine demand.

Immunization programs in MICs are more susceptible to the effects of external events.

Health systems in MICs may be poorly equipped to handle the shocks of unpredictable external events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict, and extreme weather events. Non-Gavi-eligible MICs experiencing conflict or other humanitarian crises may not have sufficient resources to allocate to vaccine procurement, new vaccine introduction, and interventions to increase coverage.

MICs have unique financing challenges in introducing new vaccines and creating sustainable immunization programs.

MICs often struggle with access to a sustainable and affordable supply of vaccine products. The price per dose offered to MICs can range substantially, with notable differences for Gavi-eligible and non-Gavi-eligible MICs. For example, HPV vaccines can cost US$2.90-5.20 per dose for Gavi-eligible and former Gavi-eligible countries and up to US$50 per dose for bilaterally negotiated prices. Poor price transparency and comparability can create unfavorable conditions for MIC vaccine investment, and it is not uncommon for non-Gavi-eligible MICs to pay 12 times more than other countries.

Non-Gavi-eligible MICs rely heavily on donor support rather than utilizing domestic resources to procure vaccines and fund routine immunization programs. Even Gavi-eligible MICs struggle to meet co-financing requirements due to domestic budget constraints. Additionally, countries that have long relied on financial and programmatic support from Gavi transition from this support when their average GNI per capita equals or exceeds an eligibility threshold. By 2030, 35 countries will have transitioned from Gavi support, which will increase their domestic vaccine financing requirements. This shift in financial responsibility often proves difficult, with many Gavi-transitioning countries struggling with the sustainability of their immunization programs.

Opportunities to Expand Immunization Efforts in MICs

To combat the unique immunization challenges faced by MICs, advocacy organizations and other critical global health partners must work together toward the following:

Technical support for MICs, especially those that are expected to transition away from Gavi support: When donor support ends, the technical immunization expertise that MICs rely on may be lost as well. Partners can better equip MICs for the future by strengthening in-country capacity for program and financial management, ensuring that countries have the knowledge, skills, and processes needed to independently implement successful immunization programs. While this type of support would be especially helpful for Gavi-transitioning countries, all MICs would greatly benefit from increased technical capacity and the establishment of NITAGs in those countries that do not currently have them.

More effective communication about the importance of vaccines: No matter how successfully a country implements its immunization program, vaccine uptake cannot be optimized without serious efforts to reduce vaccine hesitancy among parents, caregivers, and health providers. Partners can support these efforts by working with civil society organizations and other in-country groups to understand and address context-specific barriers to uptake.

Stronger and more resilient health systems: One of the many benefits of health system strengthening is increasing a country’s capacity to effectively deliver immunization services. Countries with stronger, more resilient health systems will be able to more efficiently introduce new vaccines into their immunization programs and to better withstand external events.

Increased political commitment to fund immunization programs: The sustainability of co-financing mechanisms largely depends on countries’ abilities to financially contribute to vaccine procurement and program implementation. Competing priorities both within and outside of the health space may deprioritize the importance of funding immunization efforts. Continued support from policymakers is crucial to ensure that adequate funding is earmarked in national health budgets by, for example, highlighting the return on investment of vaccines. Advocates should emphasize the role of vaccines in promoting productivity and healthy lives rather than simply preventing child deaths, as the number of these deaths in MICs has decreased over time.

Increased affordability of vaccines: Advocacy efforts should focus on increasing price transparency and working with the pharmaceutical industry to ensure that MICs can afford life-saving vaccines now and well into the future. Partners can also work to help in-country decision-makers select the most cost-effective products to optimize budgets.

Key Takeaways

Efforts to support immunization in MICs should focus on maintaining efficient implementation and high coverage of existing vaccines while working to introduce new ones. Sustainability must be emphasized to ensure the longevity of these efforts, and approaches to reach zero-dose children must be prioritized to address existing inequities. Expanding vaccine access and increasing immunization coverage for the millions of children living in MICs will be critical in reducing morbidity and mortality among this population.

-

Middle-income countries face unique challenges to immunization introduction and implementation, leaving millions of infants and children vulnerable to a range of vaccine-preventable diseases.

-

Gaps in decision-making, vaccine demand, effective financing, and access to sustainable and affordable vaccine supply, limited program capacity, and susceptibility to external events all contribute to delayed introduction of new vaccines and impact coverage of existing vaccines in these countries.

-

To support immunization programs in middle-income countries, advocates should focus on strengthening health systems and country capacity, building political commitment for domestic financing of vaccination programs, and ensuring price transparency and affordability to facilitate vaccine procurement. Vaccine demand will also have to be addressed through targeted communications efforts.

Additional Resources

Access to Immunization in Middle-Income Countries: Immunization Agenda 2030 In-Depth Review [IA2030]

New Tools to Help Middle-Income Countries Make Vaccination Decisions [PATH]

Gavi’s Approach to Engagement with Middle-Income Countries [Gavi]

Maintaining Immunizations for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in a Changing World [Annual Review of Public Health]

References

Access to immunization in middle-income countries: Immunization Agenda 2030: In-depth review. IA2030 Working Group on Middle-Income Countries. Published March 2024. https://www.immunizationagenda2030.org/images/documents/IA2030_MICBrief_5May.pdf

Cernuschi T, Gaglione S, Bozzani F. Challenges to sustainable immunization systems in Gavi transitioning countries. Vaccine. 2018;36(45):6858-6866. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.012.

Zhu J, Cole CB, Fihman J, Adjagba A, Dasic M, Cernuschi T. Opportunities to accelerate immunization progress in middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2024;42(1):S98-S106. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.079.